Disclaimer: New EUDR developments - December 2025

In November 2025, the European Parliament and Council backed key changes to the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), including a 12‑month enforcement delay and simplified obligations based on company size and supply chain role.

Key changes proposed:

These updates are not yet legally binding. A final text will be confirmed through trilogue negotiations and formal publication in the EU’s Official Journal. Until then, the current EUDR regulation and deadlines remain in force.

We continue to monitor developments and will update all guidance as the final law is adopted.

Disclaimer: 2026 Omnibus changes to CSRD and ESRS

In December 2025, the European Parliament approved the Omnibus I package, introducing changes to CSRD scope, timelines and related reporting requirements.

As a result, parts of this article may no longer fully reflect the latest regulatory position. We are currently reviewing and updating our CSRD and ESRS content to align with the new rules.

Key changes include:

We continue to monitor regulatory developments closely and will update this article as further guidance and implementation details are confirmed.

Wim Bartels is een van Europa's meest ervaren stemmen in duurzaamheidsrapportage. Met meer dan twintig jaar ervaring heeft hij meer dan 50 multinationals en beursgenoteerde bedrijven geadviseerd over ESG-strategie, assurance en openbaarmaking. Tegenwoordig brengt hij die expertise naar zijn rollen als senior partner bij Deloitte, voorzitter van de Sustainability Policy Group bij Accountancy Europe en lid van de Sustainability Reporting Board (SRB) bij EFRAG, Europa's adviesgroep voor financiële en duurzaamheidsrapportage.

In dit interview reflecteert hij op zijn overgang naar ESG, de evoluerende rol van auditors en de laatste ontwikkelingen rond de European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) en het Omnibusvoorstel.

Wim Bartels begon zijn carrière als financieel auditor bij KPMG in 1989 en sloot zich in 2003 aan bij hun duurzaamheidsteam. Hij beschrijft de overstap van financiën naar duurzaamheid als zowel uitdagend als transformerend. Vanuit een achtergrond in auditing en forensisch onderzoek vond Bartels de communicatiestijlen in duurzaamheid heel anders. "Dat was moeilijk," zegt hij. "Om op gelijke voet te komen qua communicatie... elkaar te vinden."

Even ontmoedigend was de inhoud zelf. "Ik stapte hier echt in zonder enige achtergrond," geeft Bartels toe. "Wat bedoelen we als we zeggen koolstofemissies? Dat staat niet op de balans. Ik kan het niet aanraken. Wat is het?" De overgang vereiste een volledige herlering van terminologie en concepten.

Kijkend naar het huidige landschap merkt hij op dat, hoewel het veld aanzienlijk is gegroeid, de opkomst van zelfverklaarde experts zorgwekkend is. "We hebben meer professionals nodig, niet meer 'experts'," waarschuwt hij. "Iedereen begint zichzelf na twee jaar een expert te noemen, en dat ondermijnt echte expertise."

Uiteindelijk was de verschuiving meer dan een baanverandering – het was een verandering in denkwijze. "Het kostte me een tijdje," reflecteert hij, "maar het opende een compleet andere manier van denken over waarde en impact."

Bartels ziet deze evolutie zich langs twee paden ontvouwen: wat er al gebeurt, en wat zou moeten gebeuren.

Op korte termijn zullen auditors instrumenteel zijn in het verbeteren van de kwaliteit van duurzaamheidsrapportages. "Auditors zullen ongetwijfeld meer vertrouwen geven in de gerapporteerde informatie en meer kwaliteit van de data," legt hij uit. Hun betrokkenheid – het controleren van documentatie, het controleren van reconciliaties, het signaleren van inconsistenties – verhoogt de lat voor bedrijven, zelfs als het proces nog steeds inhaalt op de complexiteit van de data.

Maar technische assurance is slechts een deel van de vergelijking.

"De echte rol van auditors zou verder moeten gaan dan het controleren van het rapport," zegt Bartels. "Ze zouden de juiste gesprekken moeten initiëren." Hij gelooft dat auditors dezelfde vooruitziende blik moeten toepassen die ze al gebruiken voor belastingplanning of liquiditeit op duurzaamheidsrisico's. Dat betekent het stellen van gerichte vragen: Zijn klimaatrisico's ingeprijsd in het bedrijfsmodel? Heeft het bedrijf een plan om te reageren?

Omdat auditors op bestuursniveau opereren, zijn ze uniek gepositioneerd om deze discussies aan te wakkeren. In Bartels' visie is deze adviesrol niet optioneel – het is onderdeel van hun verantwoordelijkheid om niet alleen aandeelhouders, maar ook de bredere samenleving te vertegenwoordigen.

Er is echter een addertje onder het gras. "Je kunt het niet in één jaar leren," merkt hij op. "Elke baan, vooral in ESG, vergt ervaring." Daarom ziet hij de huidige "pauze" die door het Omnibusvoorstel is gecreëerd als een kritieke periode – zelfs een zegen. Niet voor zelfgenoegzaamheid, maar voor het opbouwen van interne capaciteiten. Auditbedrijven moeten breed trainen binnen hun teams, niet alleen vertrouwen op niche duurzaamheidseenheden.

Bartels ziet dit moment als een cruciale kans voor auditbedrijven, maar ook als een potentiële valkuil. "Auditors hebben nu meer tijd om zich voor te bereiden," zegt hij. "Want het zou een behoorlijke uitdaging zijn geweest in de eerste een, twee, drie jaar."

Toch is hij niet helemaal optimistisch. "De eerste signalen die ik in de markt hoor, zeggen nu: 'Oh, het gebeurt niet. Dus we hoeven er geen aandacht aan te besteden. Het is alleen voor de hele grote bedrijven, en we bedienen ze toch al.'" Dit, waarschuwt hij, is de verkeerde conclusie.

"Als we dat standpunt blijven aanhouden, dan zullen we weer niet voorbereid zijn," waarschuwt Bartels. In plaats daarvan ziet hij de vertraging als een strategisch venster – een dat gebruikt moet worden om interne kennis te versterken en de assurance-gereedheid te verbreden buiten duurzaamheidsspecialisten. "Dit is het moment om voldoende mensen op te leiden, zodat we, zodra we weer opschalen in de toekomst, voorbereid zijn om een bredere groep bedrijven te bedienen."

Auditbedrijven die deze periode behandelen als een kans om institutionele kennis op te bouwen en breed te trainen, zullen beter gepositioneerd zijn wanneer de CSRD-scope weer uitbreidt. Degenen die wachten, riskeren achterop te raken – zowel in expertise als in geloofwaardigheid.

De pauze mag dan de directe druk verminderen, maar de richting is duidelijk. Zoals Bartels het stelt: "Duurzaamheid zal ook blijven. Klimaatverandering heeft niet gepauzeerd, toch? Dat gaat door."

Het Omnibusvoorstel stelt voor om de verplichte redelijke assurance onder CSRD uit te stellen. Bartels ziet dit niet als een tegenslag, maar als een noodzakelijke herkalibratie.

"Met de huidige uitdaging van auditors denk ik niet dat dat op zichzelf negatief is," zegt hij. Te snel opschalen naar redelijke assurance zou de kosten hebben opgedreven en de kloof in middelen hebben vergroot. "Het zou kritiek hebben opgeleverd dat auditors hier alleen maar geld aan verdienen. En het zou ook verdere resource-uitdagingen hebben gecreëerd."

Toch benadrukt hij dat beperkte assurance geen vrijbrief is. "Je moet er zelf zeker van zijn dat de informatie correct is," zegt hij. "Beperkte assurance is wat we doen – maar jij bent verantwoordelijk voor nauwkeurigheid en volledigheid. Dus het bedrijf zelf moet redelijk zeker zijn dat ze hoogwaardige informatie verstrekken."

Hij wijst ook op een wijdverbreid misverstand: "Veel gebruikers interpreteren beperkte assurance verkeerd. Ze denken gewoon: 'Oh, de auditor heeft ernaar gekeken, dus het is oké.'" In werkelijkheid wordt het onderscheid tussen beperkte en redelijke assurance vaak overdreven, althans in termen van perceptie.

Bartels ziet hier een strategische kans. Sommige bedrijven – zoals Philips en DSM – hebben vrijwillig redelijke assurance nagestreefd om leiderschap te tonen. "Het is een geweldige kans voor accountants om te vragen: hoe belangrijk vind je deze informatie echt? En wat betekent dat voor het externe niveau van comfort dat je eraan wilt toevoegen om je belanghebbenden te laten zien hoe belangrijk je je rapportage vindt?"

De verschuiving mag dan de druk verlagen, maar niet de verwachtingen. Kwaliteit blijft belangrijk – met of zonder assurance.

Hoe zal EFRAG bepalen welke datapunten 'minst belangrijk' zijn?

De Europese Commissie heeft EFRAG de opdracht gegeven om de ESRS te vereenvoudigen door ten minste 25% van de datapunten te identificeren en te verwijderen die als minder relevant worden beschouwd voor algemene duurzaamheidsrapportage.

Bartels schetst een stakeholdergerichte aanpak. "We zijn tot 6 mei bezig geweest met een oproep voor publieke feedback," zegt hij. "We hebben één-op-één interviews met bedrijven, investeerders, auditors, NGO's en academici om hun mening te krijgen." Het doel is om te begrijpen welke openbaarmakingen de meeste last veroorzaken of de minste waarde opleveren.

"Dat is de input voor onze verdere analyse," legt hij uit. Het doel is om te bepalen wat essentieel is – en, net zo belangrijk, wat niet. EFRAG zal ook interne criteria ontwikkelen om beslissingen te begeleiden, waarbij relevantie wordt afgewogen tegen de rapportagelast.

Bartels benadrukt dat dit proces niet alleen gaat om het schrappen van 25% van de datapunten. "Die 25% is een soort richtlijn," zegt hij. Niet alle datapunten worden met gelijke inspanning gecreëerd. EFRAG overweegt ook de kwalitatieve last, d.w.z. of het erg omslachtig en uitdagend is om de informatie te verzamelen, vooral wanneer de impact minimaal is.

De huidige focus van EFRAG ligt op het herzien van de verplichte openbaarmakingsvereisten, met bijzondere aandacht voor het mogelijk versoepelen van bepaalde "moet"-datapunten. "De nadruk zal liggen op het bepalen of sommige van de 'moet'-openbaarmakingen 'mag' kunnen worden," legt Bartels uit. "Deze verschuiving zal gebaseerd zijn op feedback van bedrijven, investeerders en andere belanghebbenden – in wezen zullen we de input gebruiken die we van de markt krijgen."

Hoewel het proces ook het herzien van vrijwillige openbaarmakingen omvat, is dat niet het hoofddoel. "We zullen ook kijken of sommige van de 'mag'-openbaarmakingen eigenlijk moeten worden verhoogd naar 'moet'," merkt Bartels op. "Bijvoorbeeld, als de meeste bedrijven ze al rapporteren, of als gebruikers consequent die gegevens eisen."

EFRAG overweegt ook alternatieve behandelingen voor de resterende vrijwillige datapunten. "Sommige van de 'mag'-punten kunnen worden omgezet in richtlijnen of anders worden gemarkeerd," voegt hij toe, waarbij hij een breder doel benadrukt om de relevantie en last van openbaarmakingsnormen te optimaliseren.

“Ik denk niet dat de structuur het probleem is,” zegt Bartels. Na aanvankelijke zorgen over het tempo van EFRAG's implementatieplanning tijdens een SRB-vergadering op 15 april, wijst hij erop dat er snel vooruitgang werd geboekt. “In iets meer dan een week zijn er aanzienlijke verbeteringen doorgevoerd en konden we het plan als bestuur goedkeuren.”

Voor Bartels toont dit aan dat de bestaande opzet in staat is om te reageren – althans op korte termijn. “Binnen de huidige SRB-structuur konden we vooruitgang boeken,” zegt hij.

Wat betreft diepere structurele hervormingen, dat ligt niet binnen de controle van de SRB. “Dat kunnen wij niet beslissen,” merkt Bartels op. “Dat is aan het administratieve bestuur of de Europese Commissie.”

De focus ligt nu op het organiseren van het werk om aan de strakke deadlines te voldoen. “We bespreken momenteel hoe we het gaan structureren in de context van de snelheid die we nodig hebben,” voegt hij toe.

“Het is heel krap,” zegt Bartels, wanneer hem wordt gevraagd of EFRAG de door de Europese Commissie gestelde deadline kan halen om de ESRS te herzien. De groep wordt verwacht snel vereenvoudigde standaarden te leveren – zonder het voordeel van een volledige publieke consultatie.

Toch blijft Bartels voorzichtig optimistisch. “We hoeven geen nieuwe standaarden te ontwikkelen – we moeten vereenvoudigen,” legt hij uit. Dat verschil is belangrijk. EFRAG heeft al een basis om van te werken. “Als we een goede aanpak hebben ontworpen om datapunten te verwijderen of interoperabiliteit te verbeteren, kunnen we relatief snel vooruitgang boeken.”

Toch erkent hij de afwegingen. “In principe, nee – we hebben niet genoeg tijd,” zegt hij. “Maar ik denk dat we het grotendeels zullen redden.”

“Het principe blijft zoals het is,” zegt Bartels. “Dubbele materialiteit – zowel kijken naar hoe duurzaamheid het bedrijf beïnvloedt als hoe het bedrijf de omgeving en samenleving beïnvloedt – blijft de basis.”

Hoewel het kernconcept niet verandert, merkt Bartels op dat EFRAG zich richt op het helpen van bedrijven om het effectiever toe te passen. “We zullen de dubbele materialiteitsbenadering onderzoeken,” legt hij uit. “De Commissie heeft gesuggereerd dat het verder verduidelijkt en vereenvoudigd moet worden.”

Dat betekent waarschijnlijk een minder formeel, minder belastend proces. “De belangrijkste kritiek is dat de huidige aanpak veel te gedetailleerd is. Bedrijven besteden te veel tijd aan het beantwoorden van vragen waarvan ze het antwoord al weten,” zegt hij. “We moeten vereenvoudigen, zonder de belangrijkste materiële kwesties uit het oog te verliezen.”

EFRAG beslist nog hoe deze veranderingen zullen worden doorgevoerd – mogelijk via een bijgewerkte implementatierichtlijn (IG1), wijzigingen in de bestaande standaarden, of nieuwe clausules die direct in het kader worden toegevoegd. “Dat moet nu nog blijken, wat de beste aanpak is,” zegt Bartels.

“Het ging inderdaad erg snel,” zegt Bartels, verwijzend naar de snelle ontwikkeling van het Omnibusvoorstel. Maar hoewel het tempo wenkbrauwen deed fronsen, ziet hij het niet als reden tot bezorgdheid. “Ik ben persoonlijk niet zo bezorgd over het proces,” zegt hij. “De Commissie begon niet pas met het verzamelen van feedback toen ze begonnen met het opstellen. Ze horen deze zorgen al twee jaar.”

Hij wijst erop dat het proces niet achter gesloten deuren plaatsvond. “Ze organiseerden een tweedaagse bijeenkomst om feedback te verzamelen van een breed scala aan belanghebbenden – niet alleen bedrijven, maar ook gebruikers, NGO's en academici,” legt Bartels uit. “En ze hebben ook met individuele belanghebbenden gesproken. Dus ja, het ging snel, maar niet in het donker.”

Die snelheid, stelt hij, moet in context worden gezien. “Zouden ze langer de tijd hebben kunnen nemen in een normale situatie? Ja, maar we bevinden ons in enigszins uitzonderlijke tijden met veiligheid, concurrentievermogen en duurzaamheid die tegelijkertijd spelen. Maar dit is een voorstel. Het gaat nu naar politieke groepen en belanghebbenden voor discussie.”

Voor Bartels weerspiegelt de verkorte tijdlijn de druk die regelgevers voelen om implementatieproblemen aan te pakken – vooral rond de rapportagelast – zonder momentum te verliezen. “Het is niet het laatste woord. Het is het begin van de volgende fase,” zegt hij.

Wat betreft de inhoud van het Omnibusvoorstel is Bartels gematigd, maar duidelijk. “In het algemeen, de vereenvoudiging – daar sta ik achter,” zegt hij. “Ik geloof dat de ESRS goed zijn. Anders had ik destijds niet getekend,” verwijzend naar zijn rol als EFRAG SRB-lid.

Toch erkent hij dat de praktische toepassing van de ESRS verder is gegaan dan bedoeld. “We moeten naar de standaarden kijken,” zegt hij. Dat is precies wat het Omnibusvoorstel beoogt: vereisten terugschalen die moeilijk te implementeren zijn of van beperkte materiële relevantie.

Over de verandering in scope – van 250 naar 1.000 werknemers – is Bartels voorzichtiger. “Dat is echt een politiek punt,” merkt hij op. “Je kunt er eindeloos over discussiëren – of het nu 100, 500 of 1.000 moet zijn.” Vanuit zijn perspectief zou duurzaamheidsrapportage degenen moeten dekken die gezamenlijk het meest bijdragen aan de economie. “Met 1.000 vang je veel. Maar als je naar de economie als geheel kijkt, zou de drempel veel lager moeten zijn.”

Toch verwacht hij dat grotere bedrijven duurzaamheidseisen blijven doorgeven in hun waardeketens. “We zullen nog steeds zien dat kleine bedrijven worden opgenomen omdat grote bedrijven erom zullen vragen,” zegt hij. “Ze zullen zeggen: 'Het is mijn strategie, en ik heb je aan boord nodig.'”

“Ik ben er vrij zeker van dat er wijzigingen zullen worden aangebracht,” zegt Bartels. Gezien de breedte van het Omnibusvoorstel en de uiteenlopende meningen binnen politieke partijen, is enige mate van onderhandeling onvermijdelijk. “Er moeten gebieden zijn waar ze zullen bemiddelen en onderhandelen,” voegt hij toe. “Gewoon omdat er uiteenlopende meningen zijn.”

“Er is veel inhoud in de voorstellen en er zijn uiteenlopende meningen,” legt hij uit. Een van de belangrijkste twistpunten is de scope – specifiek het voorstel om de CSRD-drempel te verhogen van 250 naar 1.000 werknemers. “Persoonlijk verwachtte ik dat het misschien zou dalen,” zegt Bartels. “Er is veel tegenstand geweest, ook vanuit de financiële sector.”

Maar het politieke landschap is vloeibaar. “Om eerlijk te zijn, nu ben ik niet meer absoluut zeker,” voegt hij toe. “Sommigen zeggen dat het verder omhoog zal gaan.” Het is mogelijk dat de onderhandelingen zich volledig op andere gebieden zullen richten, waarbij de scope een onderhandelingspunt wordt.

Wat duidelijk is, is dat het voorstel in zijn huidige vorm niet ongewijzigd zal worden aangenomen. “De scope-kwestie is een groot discussiepunt,” zegt Bartels – en het is slechts een van de vele die de uiteindelijke uitkomst zullen vormgeven.

“Software is een fundamenteel element voor goede rapportage in de toekomst,” zegt Bartels.

Nu duurzaamheidsrapportage meer data-intensief wordt, zijn handmatige processen niet langer voldoende. “We hebben te veel handmatige dataverzameling gezien zonder goed gedocumenteerde controles, zonder goede afstemmingen,” legt hij uit. “Veel werd gedaan in Excel, waardoor fouten gemakkelijk worden gemaakt.”

Bartels ziet software als cruciaal, niet alleen voor efficiëntie, maar ook voor nauwkeurigheid en audit-gereedheid. “Bedrijven zullen daarheen gaan om de gegevens op een efficiënte en gecontroleerde manier vast te leggen,” zegt hij.

“Zelfs als de scope omhoog gaat, blijft de CSRD.” Net als duurzaamheid: “Klimaatverandering is niet gepauzeerd.”

Voor bedrijven die eerder verwachtten onder de CSRD te rapporteren, raadt Bartels aan om inspanningen niet op te geven. “Dit is het moment om de CSRD te nemen, het te gebruiken als een managementkader, en dan te zien: waar moeten we onze strategie richten als het gaat om duurzaamheid? Waar moeten we doelen stellen? Waar hebben we een beleid nodig?”

De extra tijd moet worden gezien als een kans – niet als een pauze. “De Wave 2 en 3 bedrijven hebben nog twee jaar om zich voor te bereiden. Dat is een grote opluchting voor hen. Maar stoppen zou niet de juiste keuze zijn.”

Bartels moedigt bedrijven aan om van een compliance-mentaliteit naar een strategische mentaliteit te verschuiven. “Werk hieraan in de komende twee jaar,” zegt hij. “Wacht niet nog een of twee jaar en begin dan weer met voorbereiden op de rapportage.” Gebruik in plaats daarvan het CSRD-kader om risico's te identificeren, prioriteiten te verduidelijken en duurzaamheid in de kernactiviteiten te integreren.

Zoals hij het stelt: “Dit gaat niet alleen over rapportage. Het gaat over hoe je je bedrijf runt in een veranderende wereld.”

Understand the key changes introduced by the Omnibus Proposal and learn how to move forward with confidence under the evolving EU sustainability legislation

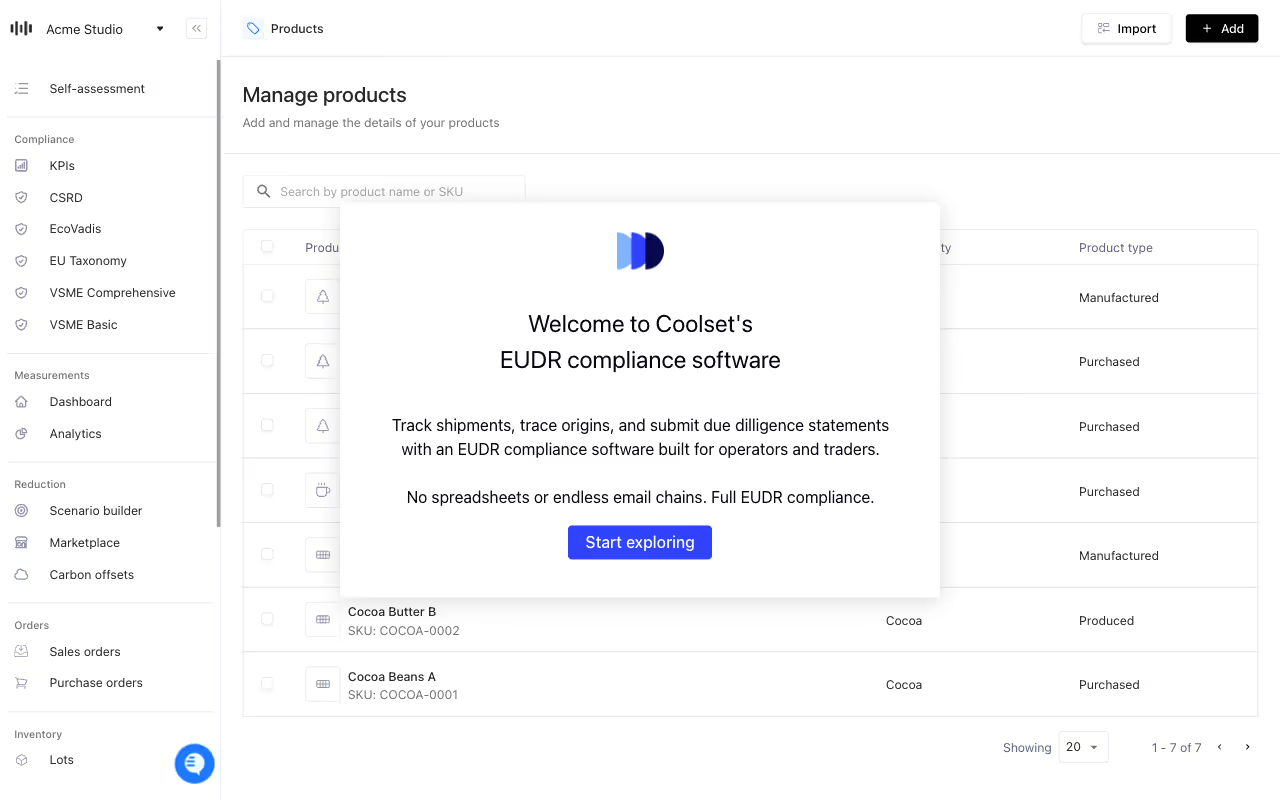

Based on customer case studies our team has developed a realistic timeline and planning for EUDR compliance. Access it here.