Disclaimer: Latest EUDR developments

On 21 October, the European Commission proposed targeted changes to the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). These adjustments aim to make the rollout smoother without changing the regulation’s overall goals.

Key points from the proposal:

We're closely monitoring the development and will update our content accordingly. In the meantime, read the full explainer here.

On July 9, 2025, the European Parliament voted to reject the European Commission’s proposed country risk classification system under the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Lawmakers criticized the list of “low,” “standard,” and “high” deforestation-risk countries for its opaque methodology and unreliable data.

The resolution passed with 373 votes in favor and 289 against, sending a strong signal that the Commission must reconsider its approach ahead of the law’s enforcement on December 30, 2025.

Despite these flaws, the European People’s Party (EPP) used the debate to revive its push for a “no-risk” category, an idea that would exempt certain countries from due diligence completely. This same proposal had passed the European Parliament in 2024 but was rejected during trilogue negotiations after facing legal concerns and strong opposition from the Council of the EU. Experts warned the measure could violate World Trade Organization rules on non-discrimination.

The Parliament's recent rejection of the risk classification system reopens debates on how countries should be assessed under the EUDR. For businesses preparing for compliance by the enforcement date of December 30, 2025, this development introduces additional uncertainty and underscores the need for robust, adaptable due diligence processes.

Under the EUDR, the European Commission is required to benchmark producer countries based on their deforestation and forest degradation risk. The idea is to scale compliance efforts based on that risk.

In practice, the system introduced three categories: low-risk countries with simplified due diligence and minimal inspections, standard-risk countries requiring full due diligence and moderate enforcement, and high-risk countries subject to enhanced scrutiny and the highest inspection rates.

Companies would still need to prove their products were deforestation-free, but the level of documentation and regulator oversight would vary based on a country’s risk score.

The Commission unveiled its first country risk list on May 22, 2025, following consultations with member states. The results startled many observers. Only four countries, Belarus, Myanmar, North Korea, and Russia, were classified as “high risk.” All four are under international sanctions or authoritarian regimes and together contribute only to 0.07% of EUDR-covered imports into the EU.

Meanwhile, some of the world’s largest deforestation hotspots, including Brazil, Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Malaysia, were placed in the “standard” category. Over 140 countries, including all EU member states, the United States, China, and Australia, were labeled “low risk.”

The results sparked immediate controversy and raised serious questions about how the classifications were determined.

The European Parliament’s rejection of the Commission’s country risk list was driven by four major concerns: flawed methodology, political imbalance, and persistent pushback from EPP.

The benchmarking system faced strong criticism for its lack of transparency and methodological flaws. The European Commission did not publish the underlying evidence or datasets used in its risk classifications, leaving stakeholders unable to verify or challenge the results. The methodology relied heavily on historic deforestation data and was not equipped to reflect ongoing degradation or recent spikes in forest loss including those occurring within EU countries. As a result, the credibility and relevance of the proposed country classifications were widely questioned, contributing to the system’s rejection.

Geographic and political imbalance

The political optics of the list raised red flags. This imbalance eroded confidence in the list. It gave the appearance of a political whitewashing: going easy on key trade partners and domestic producers, while singling out a few diplomatic pariahs as “high risk.” “Why haven’t they labeled Ivory Coast a high risk for deforestation?” asked MEP Alexander Bernhuber, pointing out the inconsistency, especially when the Commission’s own environment department had recently flagged Ivory Coast’s cocoa-driven deforestation problem.

The EPP played a central role in rallying opposition to the Commission’s risk list and in reopening the debate over a “no-risk” category. Although that proposal was included in Parliament’s 2024 position, it was ultimately dropped from the final law after EU member states objected over legal concerns, particularly potential WTO non-compliance. By rejecting the risk list, the EPP is attempting to revive the concept.

But critics, including environmental groups and opposition MEPs, view the maneuver as an effort to delay and dilute the regulation. Left-wing MEP Jonas Sjöstedt put it bluntly: “They use progressive arguments but in reality they want to tear this down… appearing to move forward while actually going backwards.”

Scenario 1: Benchmarking is revised, fix the flaws, stay the course

In this scenario, the European Commission responds to Parliament’s objections by revising the benchmarking system. The three-tier structure (low, standard, high) remains, but the data, thresholds, and transparency improve.

Key changes could include:

This would address criticisms about outdated methods and political bias. Countries like Brazil or Ivory Coast could be reclassified as high-risk, while truly low-risk nations retain simplified due diligence.

For businesses, the framework stays intact. Some sourcing regions may shift categories, but obligations remain the same: traceability, risk assessment, and compliance documentation.

Politically, this path allows the Commission to maintain the EUDR’s integrity while acknowledging valid concerns. It avoids introducing exemptions like the “no-risk” category, which failed to gain cross-party support in past negotiations.

Update:

As of the Commission’s October 2025 proposal, this scenario has not been pursued. The proposal does not include a revised country risk list and instead shifts focus to transitional enforcement and simplified obligations for certain operator types. Benchmarking reform remains possible but is no longer the primary implementation pathway.

Likelihood: Less likely. Still feasible in future enforcement phases, but currently deprioritized in favor of targeted simplifications and staggered rollout measures.

Scenario 2: The EPP pushes through a new “no-risk” category, and weakens the law

In this scenario, political pressure from the EPP succeeds in creating a fourth “no-risk” tier in the country classification system where deforestation is presumed virtually absent. Companies sourcing from no-risk countries would face little or no due diligence, skipping steps like geolocation, risk assessments, or even routine inspections.

A no-risk category would open a major loophole: without traceability, commodities from high-deforestation areas could be rerouted through exempt countries and enter the EU unchecked, a laundering risk flagged by watchdogs. It would also breach WTO rules by giving EU producers a pass while imposing full compliance on others, violating non-discrimination principles. Most importantly, it undermines the EUDR’s core purpose: ensuring all products are deforestation-free, regardless of origin.

As Greenpeace warned, “‘Zero-risk’ is a made-up concept that would be a gift to reckless companies.”

Likelihood: Possible. The Commission’s October 2025 proposal did not endorse the “no-risk” category, but internal pressure from the EPP and national ministers remains. But most lawmakers, NGOs, and legal experts remain opposed due to the implications with international trade law.

Scenario 3: The EUDR is reopened, with broader delays and dilution

This scenario goes beyond fixing the country list. The objection triggers a wider political effort to reopen the EUDR itself, potentially weakening or delaying the law. While the Parliament’s vote only targeted the benchmarking system, some actors may use it as a lever to renegotiate the regulation more broadly under the banner of “simplification.”

The Commission's October 2025 proposal did not formally reopen the EUDR, but it introduced significant delays and adjusted obligations. Large and medium operators now face a six-month enforcement grace period, while micro and small primary operators in low-risk countries may receive an extra year to comply. These are non-legislative changes, but they reflect the Commission’s response to mounting political pressure.

There were already signs of this shift earlier in the year when specific EU countries called for scaling back or pausing the EUDR.

The bigger risk is that the EUDR gets swept into a broader deregulatory push. The Commission’s ongoing “omnibus” initiatives could reopen the law, inviting lobbying that weakens definitions, delays timelines, or fragments enforcement. For businesses, this would create major uncertainty, stalling compliance efforts and eroding trust in EU regulation.

Likelihood: Increasingly relevant. While the EUDR remains intact on paper, the October 2025 proposal reflects a real softening of enforcement in response to political pressure. This scenario is no longer theoretical - it is already unfolding, even if the law hasn’t been formally reopened.

What businesses can do now?

The objection to the country risk list has created uncertainty, but the core of the EUDR remains unchanged. Companies importing, trading, or exporting cattle, palm oil, soy, wood, cocoa, coffee, rubber, or their derivatives must still comply with the regulation by December 30, 2025 (or December 30, 2026 for small and micro companies, if Commission's October 2025 proposal is adopted). Here’s how to move forward.

The enforcement starts in summer 2026. Companies should continue building due diligence systems to be ready on time:

{{custom-cta}}

Assume, for now, that all countries require standard due diligence. With the risk list under review, simplified requirements for low-risk countries may not apply at launch. This means companies sourcing from the EU, US, Canada, or other previously low-risk regions should still conduct full traceability and risk analysis. Article 10 of the EUDR already expects operators to factor in country-level risk as part of due diligence, so proactive internal scoring is aligned with the regulation.

Supply chain partners may be unsure how to proceed. Make it clear your company is preparing for full compliance. Continue requesting plot coordinates, land legality documents, and forest risk evidence. Strengthen supplier relationships now so you’re not scrambling later any future updates to the country list will be easier to integrate if you’ve already collected core data.

The rules aren’t static. The EU may release new guidance, data templates, or even reinstate a modified risk classification system. To stay compliant without redoing everything, set up your process to be modular by separating the logic for high, standard, and low risk countries in the risk assessment process, tagging shipments by origin from early in the process, and keeping a watchlist of suppliers that could result in a different risk category.

At Coolset, we’ve followed the EUDR risk list debate closely. We believe reviewing the country classifications is the right move. The original list was clearly flawed, based on outdated data, politically skewed, and disconnected from real-world deforestation trends. A proper recalibration would reinforce the law’s goals, not undermine them.

But this objection vote opens the door to three possible outcomes, some of which risk weakening the regulation itself. Coolset’s position is clear: improve the benchmarking, but resist pressure to water down the law. The idea of a no-risk exemption is a political fix to a technical problem and a risky one. It creates blind spots, weakens trust, and invites trade challenges.

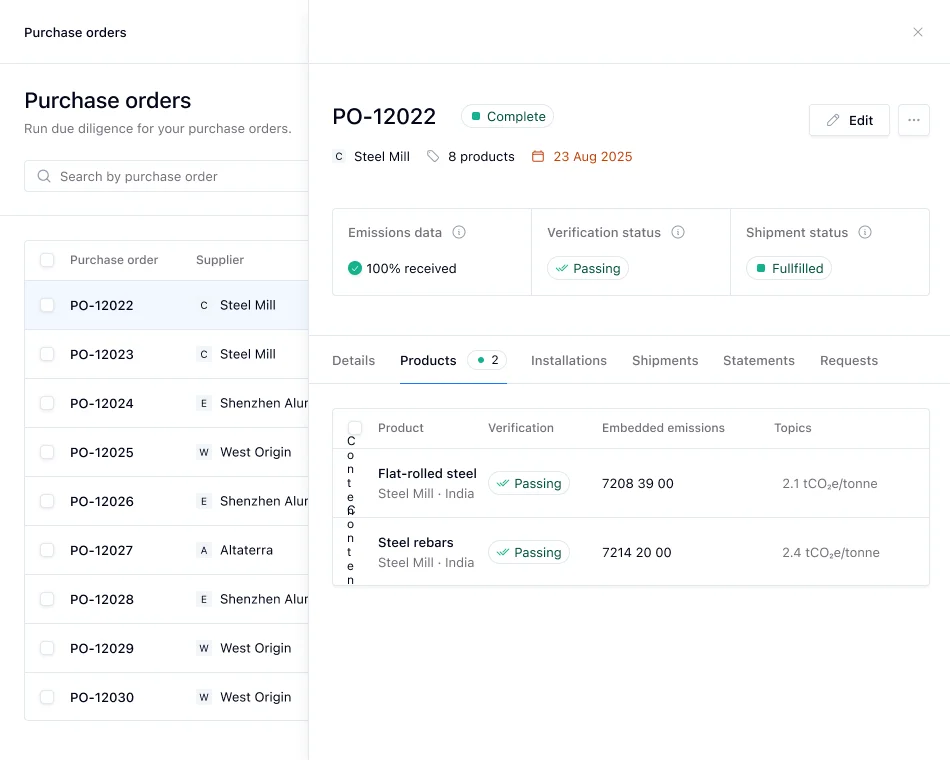

From day one, our EUDR module has included built-in country risk assessment tools, because we believe compliance should never rely solely on an external list. We encourage businesses to take the same approach: map supply chains, evaluate risk proactively, and prepare for full due diligence across all sourcing regions.

Whether the official list stays, changes, or disappears temporarily, our platform and clients are prepared because the work to make supply chains deforestation-free cannot wait. Regulation should reflect that urgency.

See how operators and traders are preparing for EUDR compliance - from supplier data collection to risk assessment and due diligence.

.avif)

Simplify the path to EUDR compliance by combining traceability, supplier-data collection and documentation in one place.