Disclaimer: New EUDR developments - December 2025

In November 2025, the European Parliament and Council backed key changes to the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), including a 12‑month enforcement delay and simplified obligations based on company size and supply chain role.

Key changes proposed:

These updates are not yet legally binding. A final text will be confirmed through trilogue negotiations and formal publication in the EU’s Official Journal. Until then, the current EUDR regulation and deadlines remain in force.

We continue to monitor developments and will update all guidance as the final law is adopted.

Als Kira Marie Peter-Hansen 2019 ins Europäische Parlament einzog, schrieb sie als jüngstes Mitglied Geschichte. Doch es ist ihre Arbeit seitdem – nicht ihr Alter –, die sie zu einer der meistbeachteten Stimmen in der EU-Klima- und Nachhaltigkeitspolitik gemacht hat.

Als Vizepräsidentin der Fraktion Die Grünen/EFA und Schattenberichterstatterin für den Omnibus-Vorschlag spielt sie nun eine zentrale Rolle bei der Verteidigung der ESG-Rahmen der EU angesichts zunehmenden politischen Drucks.

Der von der Europäischen Kommission im Februar 2025 vorgestellte Vorschlag zielt darauf ab, die Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung zu vereinfachen – hat jedoch Kontroversen ausgelöst, da er die Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) und die Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) erheblich abschwächen könnte.

Kritiker argumentieren, dass diese Änderungen die langfristigen Klimaziele der EU gefährden und Unternehmen benachteiligen, die bereits in die Einhaltung investiert haben. Peter-Hansens Führung ist entscheidend, um die Verhandlungen zu lenken und die Integrität der europäischen Nachhaltigkeitsagenda zu schützen.

Mit einem Ruf für technische Tiefe und politische Klarheit hat sie sich als zentrale Figur in der politischen Debatte etabliert. Wir haben uns mit ihr zusammengesetzt, um zu erörtern, was der Omnibus für das Europäische Parlament, die Wirtschaft und die Rolle der EU im globalen grünen Wandel bedeutet.

Auf die Frage, ob ihr Alter ihre Herangehensweise an die Klimapolitik beeinflusst, antwortet Peter-Hansen klar. Als Teil einer jüngeren Generation bringe sie zwangsläufig ein anderes Dringlichkeitsgefühl mit. „Es beeinflusst definitiv, wie ich das Thema sehe“, erklärt sie. „Klimawandel sollte für alle Priorität haben, aber ich hoffe auch, dass ältere Generationen ihre Verantwortung gegenüber ihren Kindern und Enkeln erkennen.“

Für sie sind die Einsätze nicht theoretisch. „Meine Generation wird die Kosten tragen – sowohl wirtschaftlich als auch physisch“, sagt sie. „Von der Bewältigung der finanziellen Last bis hin zur Anpassung an die Realität des Klimawandels – wir sind diejenigen, die mit den Konsequenzen leben müssen.“

Der Omnibus-Vorschlag hat im Europäischen Parlament eine ungewöhnliche Allianz hervorgebracht: Die Grünen, die Europäische Volkspartei (EVP), die Sozialisten und Demokraten (S&D) und Renew Europe haben sich verpflichtet, eine gemeinsame Position zu verhandeln, bevor sie in die Trilogverhandlungen eintreten. Zusammen halten die vier Gruppen eine parlamentarische Mehrheit – aber ob das Bündnis dem politischen Druck und den unterschiedlichen Prioritäten standhalten kann, bleibt ungewiss.

„Ich hoffe, es wird halten können“, sagt Peter-Hansen. „Der Grund, warum die Grünen für Stop the Clock gestimmt haben – und auch die S&D –, war, dass wir dieses Engagement eingegangen sind, zu sagen: Diese vier pro-europäischen Gruppen werden unser Bestes tun, um eine Einigung über den Inhalt zu finden und dies gemeinsam zu verabschieden.“

Sie beschreibt die Koalition nicht nur als strategisch, sondern als notwendig, um die Integrität der Akte zu verteidigen. „Die Alternative wäre, nach rechtsaußen zu gehen“, erklärt sie. „Das würde eine weitere Verwässerung der Gesetzgebung bedeuten. Also, auch wenn es schwierig ist, versuchen wir, die Mitte zu halten.“

Dennoch bleibt sie realistisch. „Ich weiß nicht, ob wir es schaffen werden“, sagt sie. „Aber diese Koalition ist die beste Chance, die wir haben, um die Ambitionen aufrechtzuerhalten.“

Innerhalb der Vier-Parteien-Koalition spielt Peter-Hansen eine zentrale Rolle bei der Gestaltung sowohl der politischen Koordination als auch des legislativen Inputs. „Ich bin die Schattenberichterstatterin im JURI“, erklärt sie und bezieht sich auf den Rechtsausschuss des Parlaments, der die Arbeit an der Omnibus-Akte leitet. „Und ich bin eine der Vizepräsidentinnen der Grünen. Also auch die Vizepräsidentin, die für den Omnibus verantwortlich ist.“

Da mehrere andere Ausschüsse Meinungen einbringen – von Umwelt- und Menschenrechtsfragen bis hin zu Wirtschaftsangelegenheiten –, besteht ihre Arbeit ebenso sehr in der internen Abstimmung wie in der Verhandlung. „Wir haben viele verschiedene Ausschüsse“, sagt sie. „Es ist der Rechtsausschuss, der die Arbeit leitet, aber viele der anderen Ausschüsse geben ihre Beiträge zu Umwelt, Menschenrechten, Wirtschaft.“

Ihre Aufgabe ist es sicherzustellen, dass die Grünen in all diesen Ausschüssen in die gleiche Richtung ziehen. „Ich koordiniere, dass die Grünen in all diesen Ausschüssen in die gleiche Richtung arbeiten.“

Dieses Gefühl der langfristigen Konsequenzen prägt, wie Peter-Hansen den Omnibus-Vorschlag sieht, den sie als anders als jede andere Akte beschreibt, an der sie gearbeitet hat. „Ich denke, es ist die kontroverseste Akte, an der ich gearbeitet habe“, sagt sie. „Es liegt auch daran, dass es ein Parlament ist, in dem die politischen Mehrheiten schwer zu fassen sind und die Polarisierung größer ist als in der letzten Amtszeit.“

Was den Vorschlag besonders bedeutsam macht, argumentiert sie, ist sein Timing – und die Tatsache, dass so viele Unternehmen bereits auf die nun überprüfte Gesetzgebung reagiert haben. „Besonders bei der CSRD gibt es Unternehmen, die bereits im Geltungsbereich sind, es gibt Unternehmen, die in diesem Jahr berichten sollten“, sagt sie. „Und es gibt viele Unternehmen, die auf den politischen Aufruf der Gesetzgeber gehört, ein Geschäft gemacht, ein Problem gelöst haben, und jetzt steht ihr wirtschaftliches Leben auf dem Spiel.“

Dies, erklärt sie, ist es, was sowohl die Kontroverse als auch die Einsätze erhöht. Unternehmen haben in gutem Glauben echte Investitionen getätigt, in der Annahme eines stabilen Rechtsrahmens. „Ich denke auch, was diese Akte kontroverser, wirkungsvoller macht – nicht nur in Bezug auf ihre Klimaauswirkungen –, ist natürlich, dass viele Unternehmen nach dieser investiert haben“, sagt sie. Für diese Unternehmen ist ein Rückzug oder eine Verzögerung nicht nur eine politische Anpassung – es bedroht die Finanzplanung, Compliance-Strategien und in einigen Fällen ihr gesamtes Geschäftsmodell.

Auf die Frage, wer oder was die Deregulierungselemente des Omnibus-Vorschlags vorangetrieben hat, verweist Peter-Hansen nicht auf eine einzelne Institution oder Akteur, sondern auf einen breiteren politischen Wandel, der im Europäischen Parlament stattfindet.

„Das Beängstigende ist, dass es im aktuellen Europäischen Parlament eine Mehrheit gibt, um den Großteil unserer grünen Gesetzgebung zu entfernen“, sagt sie. „Es ist keine Mehrheit, die unbedingt leicht zu nutzen ist, weil sie auf der extremen Rechten basiert. Aber es gibt eine solche Mehrheit.“

Diese Ausrichtung, erklärt sie, hat ein politisches Fenster geöffnet – eines, das genutzt werden könnte, um nicht nur den Omnibus, sondern auch den breiteren Nachhaltigkeitsrahmen herauszufordern, der in der letzten Amtszeit aufgebaut wurde. „Es gibt also natürlich einen politischen Spielraum, um unsere aktuelle Gesetzgebung in Frage zu stellen.“

Das bedeutet nicht, dass die Deregulierungsagenda leicht umzusetzen sein wird. Peter-Hansen weist darauf hin, dass diejenigen, die einen Rückzug anstreben – ob innerhalb oder außerhalb der Institutionen –, immer noch funktionierende Koalitionen aufbauen müssen. „Es ist politisch sehr kostspielig“, sagt sie. „Denn wenn die konservative Gruppe ein funktionierendes Parlament haben will, müssen sie es in der Mitte aufbauen.“

Diese politische Spannung erklärt die Struktur des Omnibus selbst. Es ist eine Akte, die schnell entstanden ist, mit begrenzter Konsultation, und als Vereinfachungsbemühung dargestellt wurde – doch ihre potenziellen Auswirkungen auf Gesetze wie die CSRD und CSDDD sind alles andere als einfach.

Peter-Hansen hat den Omnibus-Vorschlag zuvor als „massive Deregulierung“ bezeichnet. Auf die Frage, ob technische Änderungen die Akzeptanz des Vorschlags erhöhen könnten, zieht sie eine klare Grenze zwischen Anpassungen, die die Umsetzung verbessern, und Änderungen, die den Zweck des Gesetzes verändern würden.

„Ich denke, es gibt viele technische Änderungen, die notwendig sind“, sagt sie. „Wie die Vereinfachung der Datenanforderungen und der Datenerhebung – das halte ich für sehr sinnvoll. Denn es bewahrt das Ziel und die Wirkung der Gesetzgebung, macht sie aber weniger belastend. Das wäre für mich offensichtlich.“

Was sie frustriert, ist, dass solche Anpassungen über bestehende Mechanismen hätten gelöst werden können. „Ich bin etwas frustriert, dass die Kommission nicht zum Beispiel den Level-2-Akt nutzt, um einige der technischen Herausforderungen zu lösen“, sagt sie – und bezieht sich dabei auf delegierte oder Durchführungsakte, die es der Kommission ermöglichen, Gesetze zu klären oder zu verfeinern, ohne sie vollständig umschreiben zu müssen.

Doch wenn es um den Kern des Vorschlags geht, ist Peter-Hansen klar: Technische Anpassungen allein werden die grundlegenden politischen Probleme nicht lösen. „Ich glaube nicht, dass eine technische Lösung bei den politischen Problemen hilft, die ich habe“, sagt sie. „Entscheidend wird zum Beispiel der Umfang der CSRD sein, die Wertschöpfungskette in der CSDDD und die zivilrechtliche Haftung.“

Für sie sind dies keine kleinen Änderungen – sie betreffen den Zweck des Gesetzes selbst. „Das sind keine technischen Details“, sagt sie. „Sie gehen an das Herz der Gesetzgebung.“

Anders als die CSRD, CSDDD, EU-Taxonomie und CBAM wurde die EU-Entwaldungsverordnung (EUDR) nicht in den Omnibus-Vorschlag aufgenommen – obwohl sie Ende 2024 angepasst wurde. Können Unternehmen davon ausgehen, dass sie unberührt bleibt?

„Ja, das ist unsere Erwartung“, sagt Peter-Hansen. „Aber natürlich sehen wir generell Gegenreaktionen auf viele unserer Gesetze.“

Diese politische Realität lässt Raum für Herausforderungen an bestehende Gesetze, auch wenn sie derzeit nicht auf dem Tisch liegen. „Natürlich gibt es politischen Spielraum, unsere aktuelle Gesetzgebung herauszufordern“, bestätigt Peter-Hansen. „Aber politisch ist das sehr kostspielig, denn... wenn [Konservative] ein funktionierendes Parlament haben wollen, müssen sie es in der Mitte aufbauen.“

Für den Moment bleibt die EUDR in Kraft – aber Peter-Hansens Kommentare machen deutlich, dass ihre Zukunft, wie auch ein Großteil des EU-Nachhaltigkeitsrahmens, davon abhängen wird, ob politische Koalitionen standhalten.

Auf die Frage, ob es ein glaubwürdiges rechtliches Argument dafür gibt, Teile der Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) rückgängig zu machen oder abzuschwächen, nachdem sie bereits von mehr als 20 Mitgliedstaaten umgesetzt wurde, ist Peter-Hansen eindeutig.

„Nein, ich denke, die Art und Weise, wie die Kommission dies gewählt hat, ist ein bisschen empörend“, sagt sie. „Denn es ist unfair gegenüber den Wave-1-Unternehmen, die viel darin investiert haben. Es schafft Unsicherheit für Wave 2 und ein ungleiches Spielfeld für die Mitgliedstaaten, die ihren EU-Verpflichtungen nachgekommen sind, und die Mitgliedstaaten, die dies nicht getan haben.“

Über die Fairness hinaus sieht sie breitere rechtliche und institutionelle Konsequenzen. „Es schafft auch einen schlechten Präzedenzfall, wenn es um die Regulierung des Binnenmarktes geht – dass man als Mitgliedstaat einfach warten kann, um es umzusetzen.“

Sie ist besonders kritisch gegenüber der Art und Weise, wie der Vorschlag entwickelt wurde. „Kein Impact Assessment zu haben, keine Einbeziehung von Stakeholdern – ich denke, das ist das schlechteste Beispiel für Better Regulation-Prinzipien, das ich gesehen habe.“

Mit der Intensivierung der Debatte um den Omnibus-Vorschlag hat auch die Kritik zugenommen, dass EU-Nachhaltigkeitsregeln – CSRD oder die CSDDD – die europäische Wettbewerbsfähigkeit schädigen könnten. Peter-Hansen lehnt dieses Framing entschieden ab.

„Wir sehen nicht, dass das der Fall ist“, sagt sie. „Ich habe zuvor auch das Beispiel Dänemarks angeführt.“

Ihr Heimatland, argumentiert sie, ist der Beweis dafür, dass starke Nachhaltigkeitsregulierung und globale Wettbewerbsfähigkeit Hand in Hand gehen können. „Wir sind einer der am stärksten regulierten Märkte, wenn es um Nachhaltigkeitsgesetzgebung geht“, sagt sie, „aber wir sind auch einer der wettbewerbsfähigsten.“

Sie erkennt an, dass einige Beobachter Dänemarks Erfolg auf einige herausragende Unternehmen zurückführen. „Man kann argumentieren, dass es nur wegen Novo Nordisk und unseren Medizinunternehmen ist“, sagt sie. „Aber es ist auch nicht nur ein Unternehmen.“

Stattdessen verweist sie auf ein breiteres Muster: eine regulatorische Umgebung, die langfristige Wertschöpfung unterstützt, Innovation fördert und keine Kompromisse bei den Klimazielen eingeht. „Es ist ihr gesamtes Wirtschaftsmodell, das wettbewerbsfähig ist.“

Für Peter-Hansen ist dies das größere Bild, das in vielen politischen Diskussionen um den Omnibus fehlt. Strenge Nachhaltigkeitsregeln, argumentiert sie, sind keine wirtschaftliche Belastung – sie sind Teil dessen, was Volkswirtschaften widerstandsfähig, zukunftssicher und im Einklang mit globalen Übergängen macht, die bereits im Gange sind.

.webp)

Hinter den Omnibus-Verhandlungen, sagt Peter-Hansen, gibt es eine Dynamik, die heraussticht – und die für Außenstehende überraschend sein könnte.

„Nun, ich bin mir nicht sicher, ob es die Öffentlichkeit überraschen würde“, beginnt sie, „aber ich finde es interessant, wie dominant Schweden in diesem Dossier geworden ist.“

Sie verweist auf die überproportionale Rolle, die schwedische Politiker in diesem Dossier spielen. „Schweden ist eines der Hauptländer hier – weil der Berichterstatter Schwede ist, der Berichterstatter im Umweltausschuss ist Schwede, und der Vizepräsident der EVP, der dies leitet, ist ebenfalls Schwede.“

Diese nordische Dominanz geht über Schweden hinaus. „Wenn man sich das Verhandlungsteam ansieht, ist es eher nordisch oder westlich – es ist ein Däne, ein Niederländer, ein Franzose und ein Schwede, die es verhandeln.“

Im Gegensatz dazu sind südliche Mitgliedstaaten weit weniger präsent. „Der Süden Europas ist dort nicht so stark vertreten – zumindest nicht auf der parlamentarischen Seite“, bemerkt sie. „In der Kommission sind sie mit Kommissarin Ribera und Albuquerque vertreten, aber es ist immer noch ziemlich nordisch geprägt.“

Dies, schlägt sie vor, beeinflusst, wie die Gesetzgebung gestaltet wird. „Länder wie die Niederlande, Dänemark und Schweden sind in der Regel liberaler, wenn es um Regulierung geht“, sagt sie. „Auch wenn wir politisch unterschiedlich sind – grün, sozialdemokratisch oder konservativ – kommen wir oft aus ähnlichen Wirtschaftsmodellen, und dieser Hintergrund beeinflusst, wie wir Marktregulierung angehen.“

Ihrer Ansicht nach ist die Kluft nicht nur politisch – sie ist regional. „Es gibt einen Unterschied zwischen Nord und Süd, wie Regulierung gesehen wird“, sagt sie. „Und ich denke, das prägt die Verhandlungsdynamik mehr, als man erwarten könnte.“

.webp)

In der Plenardebatte am 10. März über den Omnibus-Vorschlag stellte Peter-Hansen eine gezielte Frage: Sollte die EU die grüne Wende anführen – oder dem amerikanischen Beispiel folgen?

Gefragt, welche Schritte die EU unternehmen sollte, um die Führung in der Nachhaltigkeit wiederzuerlangen, ist sie klar. „Ich denke, das Erste, was wir jetzt tun könnten, wäre, ein Ziel für 2040 zu verabschieden, damit wir für die COP-Verhandlungen in sechs Monaten bereit sind“, sagt sie.

Aber sie ist auch besorgt darüber, wie dieses Ziel verfahrenstechnisch gehandhabt werden könnte. „Ich denke, das wäre gut“, fährt sie fort. „Das ist ein weiteres Beispiel für etwas, das wir wahrscheinlich in einem Dringlichkeitsverfahren tun werden, das nicht besonders demokratisch ist.“

Über die Zielsetzung hinaus betont sie die Notwendigkeit erheblicher Investitionen. „Ich denke, es geht auch um wirtschaftliche Mittel“, sagt sie. „Und da war natürlich der Inflation Reduction Act ein gutes Beispiel. China macht dasselbe, aber die EU schafft es nicht.“

Für Peter-Hansen bedeutet echte Führung im Klimabereich mehr als nur Gesetze zu verabschieden – es bedeutet, Ergebnisse zu liefern. „Unternehmen müssen sicher sein, dass auch wenn es einen Machtwechsel gibt, die Hauptpfeiler der Gesetzgebung bestehen bleiben.“

Auf die Frage, was sie als Erstes im Omnibus-Vorschlag ändern würde, wenn sie die Chance hätte, zögert Peter-Hansen nicht: „Das wäre die Wertschöpfungskette in der CSDDD.“

Sie kritisiert die Abkehr des Vorschlags von einem risikobasierten Ansatz zur Sorgfaltspflicht. „Ich denke, vom risikobasierten Ansatz zurückzugehen und nur die erste Ebene zu betrachten, ist dumm“, sagt sie. „Es untergräbt das gesamte Ziel der Gesetzgebung.“

Ihrer Ansicht nach ist die vorgeschlagene Änderung nicht nur weniger effektiv – sie ist auch schwieriger für Unternehmen umzusetzen. „Es ist nicht risikobasiert, und es ist belastender, es auf diese Weise zu tun.“

Aber sie hört dort nicht auf. Wenn sie die Möglichkeit hätte, einen zweiten Absatz umzuschreiben, weiß sie, wohin sie als Nächstes gehen würde: „Und dann der Umfang der CSRD. Wenn ich einen zweiten wählen kann.“

Mit der Zukunft der CSRD und anderer Nachhaltigkeitsrichtlinien unter politischem Druck stellen sich viele Unternehmen dieselbe Frage: Was nun? Sollten sie mit den Vorbereitungen fortfahren oder pausieren, bis die Unsicherheit geklärt ist?

Peter-Hansens Antwort ist klar: weitermachen.

„Ich denke, die Unternehmen sollten weniger auf die politische Ebene schauen und dann tun, was sie für richtig halten“, sagt sie. Ihrer Ansicht nach bleiben die Grundlagen des grünen Wandels unverändert – unabhängig von vorübergehenden politischen Verschiebungen.

„Auch wenn die Politiker die Standards jetzt verwässern, wird die Zukunft auf grünen Lösungen basieren“, sagt sie. „Und wenn sie das Rennen mit China gewinnen wollen, müssen sie sich so oder so umstellen.“

Ihr Rat ist, über den aktuellen Gesetzgebungszyklus hinaus zu planen. Berichtspflichten könnten verzögert werden, aber die Erwartungen von Märkten, Investoren und globalen Wettbewerbern werden nur wachsen. „Ich würde Unternehmen raten, zu schauen, wo der Markt in – nicht in fünf – sondern vielleicht in 10 oder 15 Jahren ist, trotz der politischen Bewegungen jetzt.“

This free compliance checker scans your packaging documentation and maps it against mandatory PPWR data requirements, giving you a clear view of your compliance status. Get actionable insights on documentation gaps before they become compliance issues.

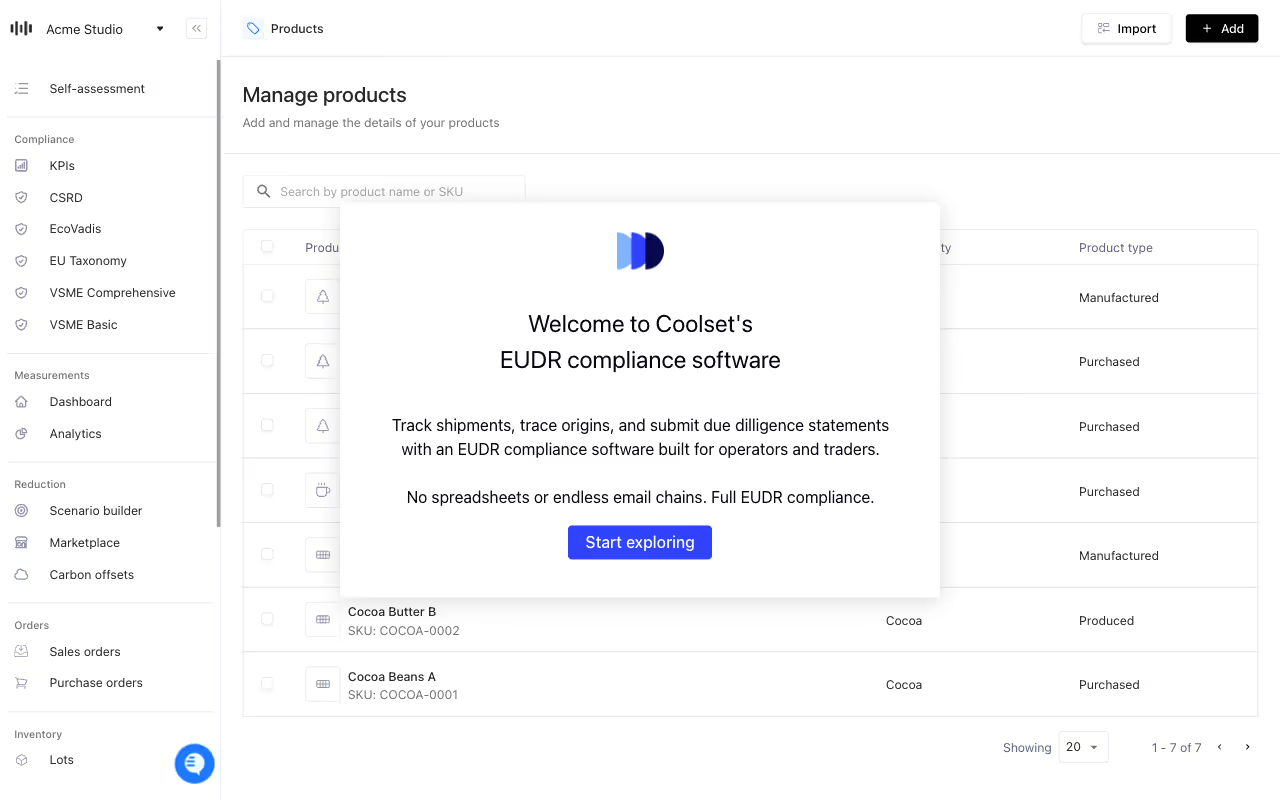

Based on customer case studies our team has developed a realistic timeline and planning for EUDR compliance. Access it here.